A very-online friend recently told me “Propaganda is anything I disagree with on Twitter.”

He was half-joking, but when I began to unpack it, I noticed I was confused about propaganda. Or rather, I noticed everyone is confused about propaganda, in exactly the way that would be most convenient for propagandists.

I am not confused by Soviet war-time posters with blocky fonts and burly factory workers, and neither are you. But if you look closely, influence campaigns are actually everywhere. Open up X, or Instagram, or TikTok, and you’re hit with a barrage of emotional information that is packaged exactly to make you think and feel a certain way.

This is not a post meant to make you question everything that you see online. This is instead a post meant to define propaganda in a slightly more useful way so that you can be aware of how it works.

From Holy Persuasion to Unholy Propaganda

The word itself comes from the latin word for propagation: the Vatican coined it back in 1622 and it literally just meant "stuff that should be spread around." Like garden seeds, or butter on toast.

It sat there as a neutral term until World War I, when governments discovered persuasion could be mass produced by copy-pasting manipulative messaging to entire populations. The occasional atrocity story (real, exaggerated, or wholly imagined) could raise armies and win wars.

This caught the attention of people like Sigmund Freud's nephew Edward Bernays. He published a little orange book, "Propaganda" in 1928, arguing these techniques were just neutral implements like kitchen utensils — useful for both serving food and stabbing.

After World War II, Goebbels, Nazi radio and 80m deaths, the word propaganda really lost favor, and, Bernays — demonstrating the very skills he taught — smoothly rebranded his work as “public relations”.

Fast forward to 1980s Reagan-Thatcher era which brought us resurgent capitalism, pantsuits, and new official narratives, but media criticism never disappeared. Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman's Manufacturing Consent (1988) claimed that new media propaganda wasn't overtly coercive but functioned instead as elite-controlled attention direction machine – less "Believe this or else" and more "Look at this shiny object over here!" This system kept people locked in a bubble of consensus, and didn’t allow unpopular beliefs to pierce the mainstream.

Perhaps illustrating exactly their point, their ideas never made it into the zeitgeist, and the media industry kept chugging along doing what it did until roughly 2009 when a company called Twitter launched a handful of features that were then copied by Facebook then copied by every social media company (hello retweet, hello feed, and hello algorithm!). Suddenly, every narrative angle was visible to everyone, as long as it was moderately salacious, outrageous or viral.

A billion new social media posts began assaulting any semblance of shared reality, and the locks held by media gatekeepers were blown apart. Most journalists also became addicted to these new tools, which began skewing much of their coverage toward the extreme.

But most critically: propaganda was now fully in the eye of the beholder. Anyone could call anything they disagreed with propaganda.

Which brings us to today, and the rather painful contemporary definition1 of propaganda, that seems to prove the point:

The deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the creator.

Sadly, here we find that the vast majority of information we consume might be called propaganda. Social media posts? Systematically served to get you to stay on site longer. Op-ed articles? Trying to shape perceptions and further the intent of the writer.

And intent? Without mind-reading powers, I can't know it. The vitamin-selling Instagram influencer might truly believe her products work miracles, or maybe she's just callously exploiting people’s fear of death. I don't have special access to a senator's thoughts when he gives a press conference, but if I think he’s pandering, it’s easy to dismiss his every drawl as a callous attempt at making me feel a certain way.

Here’s the tricky thing about propaganda: we tend to view propaganda as any attempt at persuasion we can plainly see as persuasion. If it’s not visible to us, it’s just good marketing. This means we’re essentially in an arms race with the rapidly developing methods of obfuscating persuasion. (And yes, this is a dark thought.)

For this reason I'm sympathetic to people who label mainstream media “propaganda.” The painful editorial meetings, grinding fact-checking work that goes on behind the scenes is just not visible to them. To make matters worse, most people don’t know the important distinction between straight news and opinion writing. (And to be fair, not everyone with "journalist" in their social bio adheres to these standards.)

Let me widen the lens here for a moment and make a case that propaganda can be understood as something else — that you can point to it when it happens, and that you’re more familiar with it than you think.

The Subtle Harvest of Unexamined Beliefs

When other people want us to believe a certain thing, they will look to our squishy sensitive parts first. And the beliefs that matter—the ones easiest to manipulate—are those connected to our existing biases.

Propaganda is usually successful when it grafts ideology onto our unexamined, deeply-held intolerances and prejudices. A fear of outsiders can be grafted onto a politically resonant message of “migrants are stealing our jobs,” playing into both economic insecurity and light xenophobia. While this new belief about job theft is theoretically testable, the goal of the propagandist is to keep an idea from being examined, verified, or challenged. It works by short-circuiting our critical thinking — activating our amygdala, not asking for analysis.

I think propaganda can be best understood this way:

Any attempt to shape perceptions while avoiding or evading meaningful self-correction.

Unlike journalism or scientific inquiry—which strives to acknowledge and correct errors—propagandists typically dodge accountability, flood the information space with confusion, or double down on falsehoods.

Is this a big difference? I think it might be.

The Way Propaganda Acts

There are many, many, many sophisticated strategies that modern propagandists use to confuse us. Here are just a few:

Proportionally misrepresenting a factual thing that happened, and using that as justification for drastic action. When people say stuff like “Someone was killed by an X (Immigrant/weapon-type/toothbrush), therefore we should ban all X’s”, meanwhile X’s actually only kill someone in 1/1,000,000 cases.) This obfuscates the idea of acceptable risks and makes good policy impossible to implement.

Flooding the Zone with Shit: Pushing so many contradictory narratives that no one can tell what the hell is going on. This is one of the most effective kinds of propaganda today because it uses asymmetry of distribution to win: Corroborating and debunking claims is slow and expensive. Making up dozens of different bullshit claims is fast and cheap. The goal here is to obfuscate, confuse, and erode trust in any reliable information source.

In 2014, a Russian missile shot down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 in Ukraine killing 298 people. Russian media flooded the public with dozens of contradictory theories—blaming Ukrainian forces, claiming a plot targeting Putin’s plane, or alleging a false flag with pre-loaded corpses. The intent was to bury the truth in confusion, neutralizing fact-checkers through sheer volume. It worked. (You might notice that this is also an effective political strategy for running a government.)

The Big Lie: Strangely the bigger and more tempting the lie oftentimes the more powerful it is, particularly if you can make it a conspiracy. This is notable because you’d assume it’s easier to confuse people about small things, but a massive lie — if it appeals to the right bias, identity group, and disposition — can actually end up metabolizing more like a religious belief: something unquestionable because it provides people with so much value.

A few other useful, but not definitive, flags for propaganda are: Identity-signaling (us vs. them), and the classic dehumanization playbook: (calling opponents “vermin,” “scum” etc.).

Tests for Propaganda

The most useful frame for identifying propaganda is looking for obfuscation. This is helpful because there is, hypothetically, a system that can be applied to falsifying it. Specifically, it asks the consumer of information to check actual claims, not just vibes.

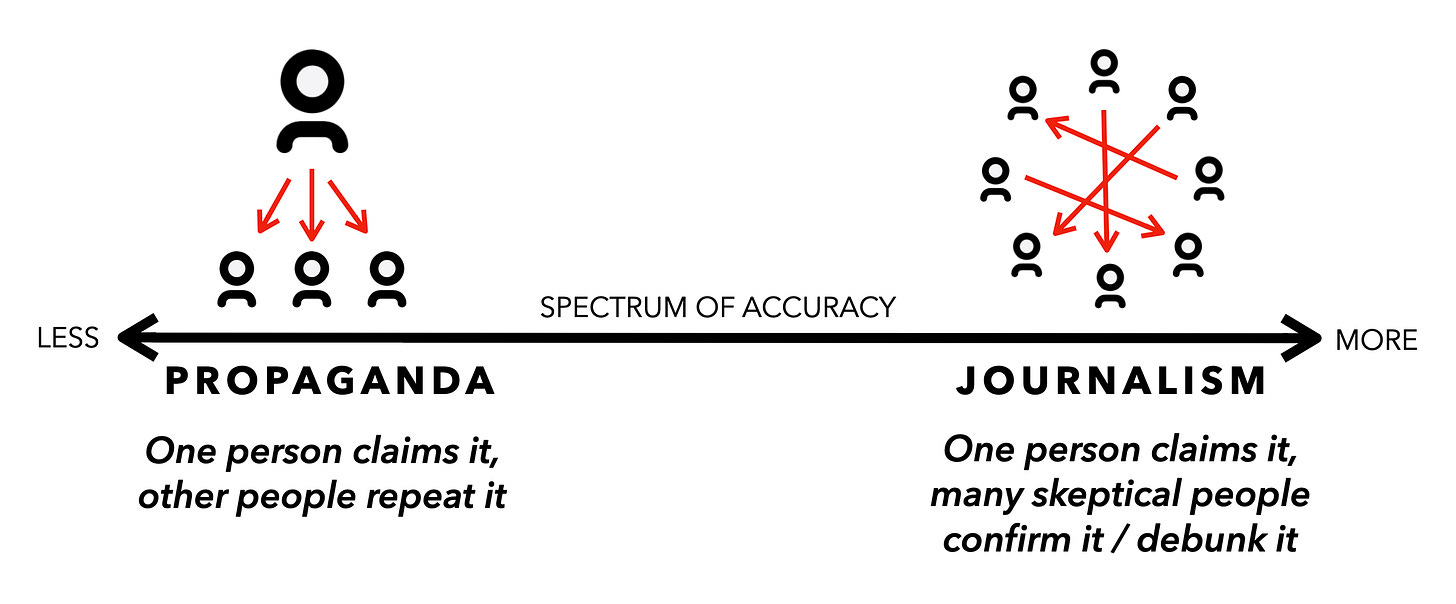

I find it helpful to put information on a spectrum — one that corresponds to the number of skeptical people that have a chance to confirm/debunk a claim.

This is journalism in a nutshell — the more pedantic, transparent, dogged and annoying people you have looking at a claim, the more likely that claim is to be mostly, factually true.

The makeup of those individuals is important, and the standards they use to confirm/debunk something need to be pretty strict. Most traditional journalists have been in newsrooms that share these protocols. These are real guidelines that people can and do lose their jobs over. Scientists have even stricter standards.

But again — how do you know this? Well, you kind of have to trust them — but you shouldn’t. Instead, you can look at their behavior over time. And to do this, there is one very very very important thing that separates propagandists from other creators of media: the correction cycle.

The Sources That Can Admit Mistakes

When The New York Times publishes something wrong, it publishes a correction. When the science journal Nature publishes something wrong, it issues a retraction. When someone updates a Wikipedia entry, its edit history is publicly updated. Their credibility isn't derived from perfection, but from their commitment to a self-correcting process.

I think this shows one of the more meaningful distinctions between journalism and propaganda: the way they handle errors. The most reputable news organizations keep a running tab on corrections, and plainly state these policies in ethics guidelines.

Keep track of the reputational capital that organizations and people expend to correct the record when they are wrong. If they expend it with specific corrections and have a system in place to do it, they are less likely to have propagandistic tendencies.

What makes this possible is that professional news organizations live within a system of active accountability. For big-ticket news items, if one news organization gets the facts wrong, another organization will call them out for it.

This creates a real informational fingerprint — the number of critical waypoints a piece of content hits before it reaches you. Journalistic (and scientific) institutions maintain credibility not through flawlessness but through fairly transparent error-handling mechanisms. Their corrections aren't evidence of failure but of an immune system working as intended.

In contrast, propagandists generally do not acknowledge errors. When forced to, they typically:

Pretend the correction represents no meaningful change ("We've always been at war with Eastasia")

Misdirect or say it’s unknowable (“Well maybe it’s this instead”, or “I don’t know anything about that error”)

Attack those who pointed out the error ("Enemy of the people!")

If you’re trying to tell the difference between propagandists and other media, look for a willingness to admit mistakes, and for meaningful changes they make if a story is retracted. This is what we might call a “meta-indicator” — not evidence itself, but a good signal that a news organization is hewing closer to reality.

Beware The Double Standard

Skillful propagandists will often use any hint of error to try and discredit the entire fact-finding process itself. (“You see they were wrong about that thing they corrected, you can’t trust them at all.”). The goal here is to cast doubt, muddy the water, and confuse the agenda. But they will not apply this same standard to themselves.

Each correction threatens the entire edifice of authority, so they simply will not issue them unless it’s in service of making another point. That's why propagandists invest tremendous energy in avoiding admitting, reflecting, or cataloging errors.

The irony is that this makes propagandists simultaneously more confident-seeming and more brittle. They project certainty while being unable to incorporate new evidence that contradicts prior claims. Error correction is necessary for solving problems effectively, and without it, they are more prone to making mistakes.

You have been a propagandist at some point too

A while back, I carried a fact in my head that was wrong. I was sure that ocean waves (the crashing, foaming kind that surfers ride) were caused by the moon’s gravity.

This is not true. Most waves are caused by wind friction. Tides are caused by the moon’s gravity — a fact I misheard and confabulated into waves at some point when I was very young. (It’s okay if you heard the same thing.)

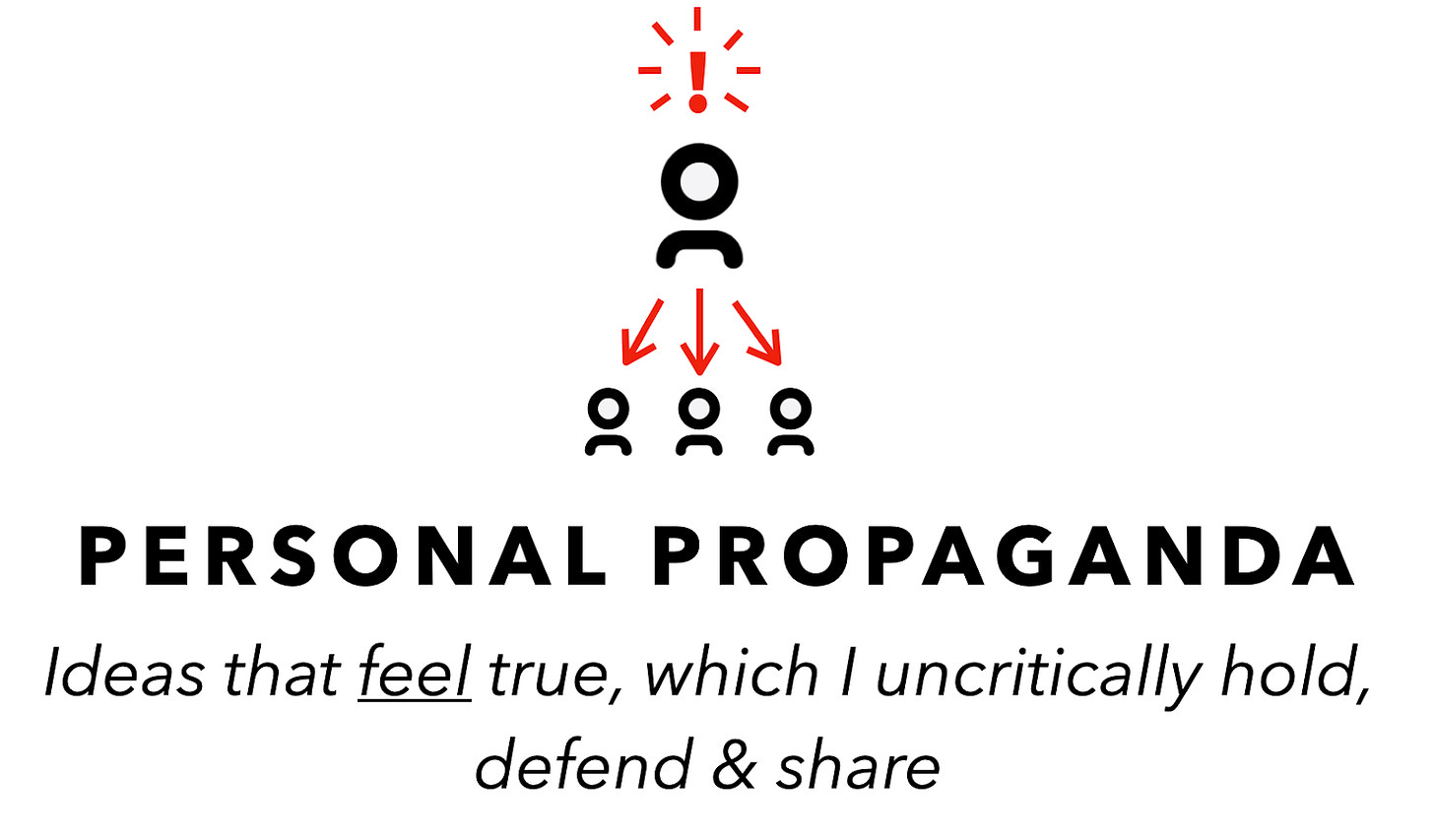

This moon misinfo lived in my mind rent-free for a good portion of my life. When questioned by a friend, the “fact” had been there so long that I began spinning up an elaborate physics explanation of it in real time trying to explain how it worked. I categorically defended my lunar wave theory with gusto before sheepishly conceding I was mistaken.

Now this was not an important fact to me, which made it easy to update. But we are all propagandists about a subset of our deeper biases, even if they are not true. We instinctively double down on the precious narratives we hold, ideas our social circles embrace, or the emotionally resonant concepts that simply feel satisfying. This sort of self-gaslighting is common, and it probably served our ancestors quite well. It helps to believe we're careful, moral beings with flawless rationality, even when we are not!

Good propagandists will try to slide between our mental defenses and offer information that subtly confirm an existing prejudice because they know we will then defend them aggressively. Part of us wants these ideas to be true, even if the evidence says otherwise.

This is one of the reasons why social media is so good for propaganda and bad for reality. It gives the cheat codes to anyone’s personal propagandist. You can pass-on something that feels true, and rather than hitting the hard earth of corrective accountability in real life — posting it online will earn you a lot of likes, shares and follows from people who believe the same thing.

This quickly forms superclusters of people who reinforce each-other’s incorrectly-held beliefs, build identities around them, and ultimately make voting blocs that hold false ideas that need to be accommodated. (Note that this happened without social media, too — it just happens much more efficiently today!)

Information is highly transmissible, and a sticky concept can transit between people like a virus (we should probably have a word for that). So a bad idea/terrible fact can find its way into the mouth of a normally reliable person by accident. The steps from Russian state media to podcast host to dinner table conversation are surprisingly short.

It’s why the “useful idiot” role is such an important role in psychological operations. All of us can fall prey to becoming the useful idiot in someone else’s propaganda—parroting ideas that “feel right” without realizing we’re amplifying messages that benefit propagandists.

Can you make propagandists less bad?

Actually, yes. Sometimes.

Propagandists are playing a game of chicken with the people who are calling out their mistakes or lies. To make a propagandist stop spouting misinformation requires accountability. When I was fact-checked by a friend about moon waves, I was forced to update my position. Politicians are sometimes forced to update theirs in the same way when called out by journalists in public.

But for these systems to work, they need authority from one of two non-exclusive places: large audiences or reputation.

During Walter Cronkite’s heyday, being on national TV carried a built-in incentive to avoid outright lies. These gatekeepers had plenty of flaws, but they did enforce at least a basic standard of truthfulness. If you wanted to speak to the public, you had to meet those standards; you couldn’t just spout falsehoods and still expect reasonable coverage.

Today, we have half a dozen social media algorithms acting as similar attention monopolies. They actually have tremendous power in determining what people think is true. In 2022, the Biden administration tweeted a falsehood about job numbers, and got fact-checked by Twitter’s fact-checking system, Community Notes, prompting an actual retraction.

We need fact-checking systems integrated with social media that can transparently maintain public trust. This is not as difficult a problem as you might assume. These tools are currently too slow and too conservatively triggered to make a difference in how people consume information. But they can—and must—be improved (some sketches of ideas on this here).

But there's a final dimension here that really matters: reputation. Reputation functions as evolutionary pressure on the source of ideas. The most reliable propaganda detection method combines these elements: "What happens when this source is proven wrong, and what reputational price do they pay?" If the answer is obfuscation and none, they are less likely to be telling you the truth.

In the end, the propagandist's greatest weakness is their inability to admit when they are wrong—and our greatest strength is recognizing when they can't.

Thanks for reading. If you’d like more ideas like this but in book form, Outrage Machine is available here, or on Audible here.

Definition from Propaganda and Persuasion

https://www.amazon.com/Propaganda-Persuasion-Garth-S-Jowett/dp/1412977827

Brilliant piece - going onto my sensemaking workbench. Thanks!